At the bottom of this blog are resourceful podcasts.

By Linessa Farms LLC

Coccidia is one of those topics that causes confusion because most people picture parasites the same way — something living in the gut, stealing nutrients, and easily handled with a dewormer. Coccidia is different.

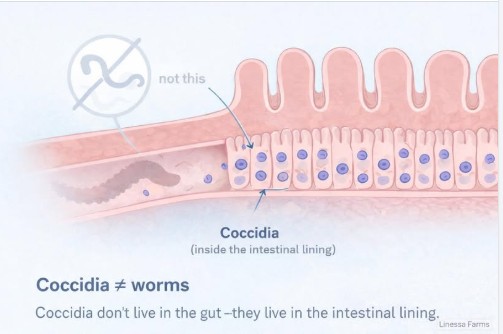

Coccidia are protozoan parasites, not worms. In sheep and goats, the organisms involved are primarily Eimeria. These are microscopic, single-celled organisms, not visible parasites living freely in the gut. A quick clarification that matters: coccidia are the organism; coccidiosis is the disease. Many animals can carry coccidia without ever developing coccidiosis. That distinction matters more than people realize. Unlike worms, coccidia are intracellular parasites. They don’t float around in the intestinal contents. They invade the cells lining the intestine and reproduce inside those cells as part of their life cycle.

This is why:

• standard dewormers don’t work

• fecal results can be misleading

• animals can have exposure without obvious illness

Most sheep and goats are exposed to coccidia early in life. Low-level exposure is normal. Adult animals often carry small numbers without showing disease. Presence alone does not automatically mean something is wrong. Problems show up when exposure, stress, and immature immunity overlap — which is why coccidiosis is primarily a disease of young lambs and kids, especially during stress windows, such as:

• weaning

• weather changes

• crowding

• inconsistent nutrition

• wet or contaminated environments

One of the most common mistakes is thinking of coccidia as a “worm problem” that just needs the right product. It isn’t. To manage it well, you first have to understand how it actually works.

Coccidia have two jobs:

survive outside the animal — and multiply inside the intestine. Coccidia leave the animal in manure as oocysts (think: a tough, protected capsule). At this stage, they cannot infect anything yet. Once manure sits around with moisture, air, and time, those oocysts change into an infective form. This is why wet bedding and dirty pens matter so much.

Young animals pick them up from bedding, feed contamination, water, or licking surfaces. Small exposures happen all the time. The problem is the amount and timing of exposure, not simple presence. After being swallowed, coccidia enter the cells lining the intestine, mainly in the small intestine, and begin multiplying.

As they multiply, those cells rupture and neighboring cells are damaged. This is where growth issues often begin — sometimes before diarrhea ever appears. New oocysts are then passed in manure, and the cycle repeats. One key takeaway (very important)

Coccidia doesn’t live in the gut — it lives in the intestinal lining, and the environment determines how big of a problem it becomes. This life cycle is why coccidia is a management problem first, and a medication problem second.

Where the damage happens:

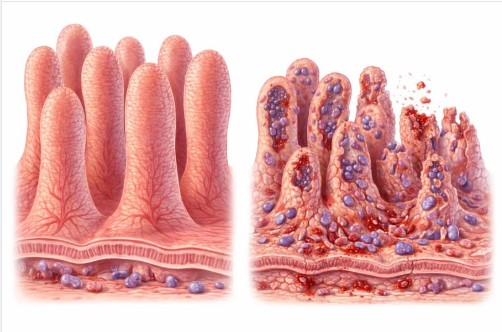

In sheep and goats, coccidia primarily affect the small intestine, especially the sections responsible for nutrient absorption. Once ingested, coccidia invade the cells lining the intestine and begin multiplying inside those cells. As the organisms reproduce, those cells rupture and die. Neighboring cells are then infected, and the cycle continues. This isn’t irritation of the gut contents. It’s structural damage to the intestinal surface itself.

Why signs don’t always match the damage:

This is where people get tripped up. By the time you see obvious diarrhea, a lot of damage has often already occurred. In some cases, diarrhea is mild or short-lived. In others, it may never be dramatic at all.

What you often see instead is:

• poor growth

• dull hair coat

• inconsistent manure

• animals that eat but don’t gain

• lambs or kids that look “weeks younger” than their penmates

This is the classic failure-to-thrive pattern.

Why timing and amount of exposure matter so much:

Coccidia reproduce very quickly once inside the intestine. Small exposures spread out over time are usually tolerated and help build immune control. The problem is high or repeated exposure over a short period, especially during stress windows like:

• weaning

• weather changes

• crowding

• diet shifts

It’s rarely one bad exposure. It’s too much, too fast, at the wrong time. That’s when the intestine takes the biggest hit — often before anyone realizes there’s a problem.

What happens after the damage is done:

Here’s the part that causes the most confusion. The intestinal lining does turn over, and some recovery can happen, especially if the damage was mild or short-lived. But regrowing cells does not always mean the intestine goes back to normal. Think of it like a roof. You can replace damaged shingles, but that doesn’t mean the sheeting or framing underneath wasn’t warped or weakened. The roof looks better, but it may never perform the same way again. The intestine works the same way. Cells can be replaced, but the overall surface area and efficiency don’t always fully recover after severe or repeated damage.

That’s why some lambs and kids:

• stop scouring

• look brighter

• resume eating

…but still:

• grow slower

• struggle with feed efficiency

• never quite catch up to their peers

You don’t “fix” damaged intestine. You manage what’s left. Why treatment alone often disappoints:

By the time coccidiosis is obvious:

• the most damaging phase has usually already happened

• treatment may stop further replication

• but it cannot undo lost intestinal structure

This is why late, blanket treatment so often feels ineffective — and why prevention matters far more than rescue.

The key takeaway:

Coccidiosis isn’t just a short-term diarrhea problem. It’s a developmental injury that can permanently change what an animal’s intestine is capable of doing.

This part is about the question people keep asking, even if they don’t say it out loud:

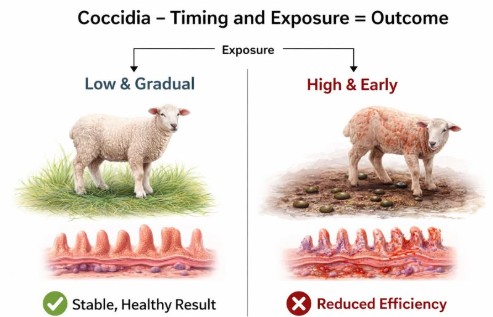

Why do animals in the same environment have such different outcomes? The answer usually isn’t luck. It’s exposure pressure and timing. Exposure is normal. Disease is not. Coccidia are everywhere sheep and goats are. Exposure alone does not mean disease.

Coccidiosis happens when:

• exposure is too high

• exposure happens too early

• or exposure happens during a stress window

This is why “it’s everywhere anyway” is true — but incomplete. Why timing matters so much.

Young lambs and kids are still:

• developing their intestinal lining

• learning how to regulate inflammation

• building immune recognition

If heavy exposure happens before those systems are ready, intestinal damage can occur that can’t be fully undone later. That animal may survive. It may even look better after treatment. But its efficiency and resilience can be permanently reduced. Why pressure matters more than presence.

Exposure pressure builds when:

• moisture is high

• stocking density is tight

• manure accumulates in high-traffic areas

• stress and exposure stack together

Low, gradual exposure is usually tolerated. High or repeated exposure over a short period is what causes problems. It’s rarely one bad exposure. It’s too much, too fast, at the wrong time. Why problems tend to come back.

Animals with prior intestinal damage often struggle again when:

• grass is lush and wet

• intake rises quickly

• weather stress increases

• nutritional demand goes up

This isn’t a “new infection from scratch.” It’s a system with less reserve being asked to do more. Where whole-group treatment fits into this. Medications can reduce replication and help animals through high-risk periods. They have a role.

But here’s an important reality check:

If you’re having to repeatedly treat the entire herd or flock, that usually points to a system or site pressure issue — not a failure to control coccidia.

Repeated whole-group treatment is often a signal that:

• exposure pressure remains high

• environmental conditions haven’t changed

• timing and grouping still need attention

Medication can’t compensate for a system that keeps pushing animals past their tolerance threshold.

The takeaway-Coccidia isn’t about elimination. It’s about managing exposure during critical windows.

When pressure is kept reasonable:

• most animals handle exposure

• fewer develop disease

• fewer carry long-term consequences

That’s what real control looks like.

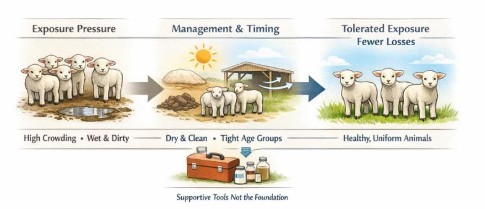

By now, most people following this understand a few core ideas:

• Coccidia are not worms

• You don’t eliminate them

• Timing and exposure pressure matter more than treatment alone

So the last question is the one that actually matters:

What actually reduces losses and long-term damage?

It isn’t one product. It isn’t a schedule. And it isn’t repeatedly treating the entire herd or flock. What moves the needle is reducing exposure pressure during vulnerable windows. That usually means looking upstream, not reaching for another bottle.

What consistently makes a difference? Across farms, systems, and years, the same factors show up again and again:

• Tight age groups

Wide age spreads create a constant exposure ramp. Older animals shed more; younger animals take the hit.

• Dry footing and clean traffic areas

Waterers, feeders, creep areas, jugs, and corners drive exposure far more than pasture does.

• Avoiding stacked stress

Weaning, diet changes, weather swings, hauling, overcrowding — stacked stress lowers tolerance fast.

• Targeted response instead of blanket reaction

Early recognition and treating the animals that actually need help works better than treating everyone late. When pressure stays reasonable, biology does the rest.

-A word on medications (because it always comes up)-

People will commonly encounter the following tools when coccidia is discussed:

• Amprolium (Corid®)

• Decoquinate (Deccox®)

• Ionophores (Rumensin®, Bovatec® — where labeled and appropriate)

• Toltrazuril / Diclazuril

• Sulfas (historically)

These products do have a place. When used correctly, they can reduce parasite replication and help limit clinical disease.

But they all share the same limitation:

They reduce organism load — they do not fix exposure pressure.

Corid, for example, interferes with thiamine uptake in the parasite. That can slow replication, but it doesn’t address why exposure was overwhelming in the first place — and it doesn’t repair damaged intestine. The same limitation applies to every product on this list. This is why results vary so widely between farms using the same medication. Medications tend to work best when:

• exposure pressure is already being managed

• age groups are tight

• stress isn’t stacking

• and treatment is used to support animals during known risk windows, not as a permanent solution

*If you’re having to repeatedly treat the entire herd or flock, year after year, that usually points to a system or site pressure issue, not a failure of the medication itself.*

That’s not blame. That’s information!

-A quick note on the environment-

Coccidia oocysts are very resistant in the environment, which is why “cleaning harder” often doesn’t work. Many common disinfectants — including bleach — are not very effective against coccidia oocysts. Freezing doesn’t reliably eliminate them either.

What does matter is changing the environment so oocysts are less likely to survive and build up:

• keeping areas dry

• reducing manure accumulation in high-traffic zones

• limiting crowding

• allowing sunlight and drying where possible

This is another reason coccidia control is a systems problem, not a sanitation contest.

You don’t win by killing everything. You win by lowering exposure pressure.

-What success actually looks like-

Real coccidia control doesn’t look dramatic.

It looks like:

• consistent growth

• fewer setbacks during stress

• animals staying closer to their peers

• less reliance on rescue treatments

It looks boring — and boring is good.

Coccidia isn’t about elimination. It’s about keeping pressure low enough that biology can do its job. Tools belong inside a functioning system — not in place of one.

Below are linked podcasts Goat Talk with the Goat Doc

Enteric Protozoa Part 1 : Coccidia

Enteric Protozoa Part 2: Other Guys

Below is a linked podcast from Ringside: An American Dairy Goat Podcast

Understanding Extra-Label and Illegal Drug Use in Dairy Goats with Dr. Katie Jackson DVM